Ten years ago today, three groups of men launched a spate of coordinated terror attacks, killing 130 people in Paris.

It remains the worst terrorist atrocity on French soil and the deadliest in Europe since the Madrid bombing in 2004. A decade on, we look back at how events unfolded and led to the Brussels terrorist attacks just a few months later, in March 2016.

For many people in France, the attacks of 13 November 2015 remain an open wound. The memory of the Islamic State's coordinated strikes in various locations, including the Stade de France stadium and the Bataclan concert hall, is still raw.

Paris was plunged into chaos on a grim autumn Friday night when three rental cars carrying three ISIS teams swept through the city armed with automatic weapons and suicide vests.

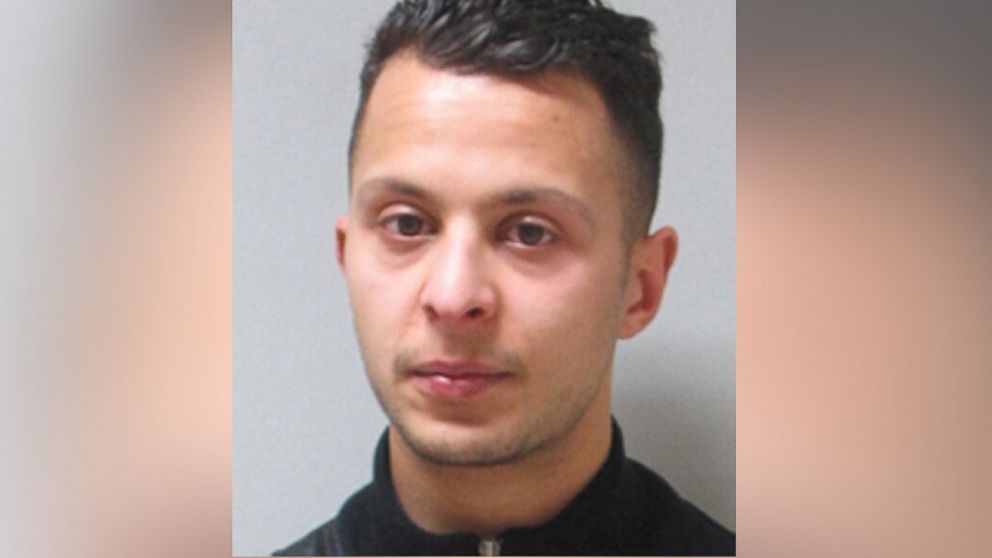

Just before 9 p.m., a Renault Clio driven by Belgian-based plotter Salah Abdeslam stopped outside the Stade de France, where 80,000 people, including President Francois Hollande, were watching France play Germany.

Three attackers got out. Two were Iraqis posing as refugees. One was a French-Belgian radical, Bilal Hadfi. All wore crude explosive vests packed with shrapnel.

They failed to get inside the stadium. Minutes later, as Abdeslam drove away with his unused vest still in the car, the first bomber blew himself up outside Gate D at 9.20 p.m., killing one person. Two more blasts followed around the stadium.

The Renault Clio driven by Belgian-based plotter Salah Abdeslam stopped outside the Stade de France. Credit : Belga/AFP

A police officer directs people outside the Stade de France stadium during the international friendly soccer France against Germany, in Saint Denis, outside Paris. Credit : Belga/AFP PHOTO/1603011801

Meanwhile, a black Seat Leon carrying ringleader Abdelhamid Abaaoud and his gunmen, Brahim Abdeslam and Chakib Akrouh, was moving through the café-lined streets. At 9.25 p.m., they opened fire on packed terraces near Rue Bichat, killing 13.

Over the next 15 minutes, they hit more bars around Place de la Republique and La Belle Equipe, killing dozens more before Brahim blew himself up in a café. Abaaoud and Akrouh abandoned their car and slipped away.

Abdelhamid Abaaoud, a Belgian ISIS operative, rises through ISIS ranks in Syria and is tasked with organising attacks in Europe. Credit: Belga

At almost the same time, three French ISIS fighters pulled up outside the Bataclan concert hall. At 9.42 p.m., they sent a final text to Brussels saying, "We're getting going; we're starting." Minutes later, they stormed inside, shooting randomly.

Eighty-nine people were murdered in the first 20 minutes. Survivors said the attackers spoke perfect French and bragged they were avenging French airstrikes.

Local police managed to kill one gunman, whose vest detonated as he fell. The remaining terrorists took hostages until elite RAID units stormed the building just after midnight, killing the pair.

A survivor near Bataclan. Credit : Le Parisien

By dawn, seven of the ten-man squad were dead. Only Salah Abdeslam, Abaaoud and Akrouh had escaped.

In the days that followed, tension in Brussels began to build. Belgian authorities feared that some of the surviving attackers, including Salah Abdeslam, the only member of the Paris commando still alive, had slipped back across the border and were hiding in the capital.

On Friday, 20 November, Belgium's security council raised the terror threat level in Brussels to Level 4, the maximum. Officials warned of an "imminent and serious threat" of a coordinated attack, possibly targeting shopping centres, public transport or crowded areas.

What followed was something unprecedented in peacetime Belgium: an entire European capital going into lockdown.

By Saturday morning, the metro network was closed, trams and buses stopped running, and schools, universities, cinemas, and even Christmas markets shut their doors. Soldiers in camouflage patrolled the streets with automatic rifles. Armoured vehicles stood outside government buildings and hotels.

The atmosphere was tense but eerily quiet. Residents were told to stay indoors and avoid large gatherings, while cafés and restaurants in popular districts like Ixelles, Saint-Gilles, and the city centre were deserted. At night, the sound of helicopters circling overhead became the city's new background noise.

The government held daily press conferences, giving sparse updates but few concrete details. Prime Minister Charles Michel appeared alongside police and military leaders, trying to reassure the public that the measures were necessary to prevent "a serious and imminent attack."

Picture shows military personnel patrolling the streets of Brussels, in the 'Operation Vigilent Guardian' anti-terror mission in Belgium, Tuesday 24 December 2019. Credit : Belga/James Arthur Gierke

Social media played its part. When Belgian police launched overnight raids in search of suspects, they asked citizens not to share information or photos online that might alert terrorists to the movements of security forces.

In response, Belgians flooded Twitter with pictures of cats, a light-hearted act of solidarity that became a symbol of the national mood: anxious, yes, but quietly defiant.

The lockdown lasted four days, from 21 to 25 November. On Wednesday morning, when schools reopened and the metro resumed partial service, the relief was palpable.

Business owners spoke of huge losses, and many residents described the experience as surreal, "like waking up in a ghost city."

In the days that followed, investigators traced calls, false passports and safe houses across Belgium. Abaaoud hid in scrubland near Paris before his cousin, Hasna Ait Boulahcen, tried to help him find shelter.

Police, tipped off by an informant, tracked them to a flat in Saint-Denis. In a fierce raid on 18 November, Akrouh blew himself up, killing Abaaoud. Boulahcen suffocated in the blast.

Snipers of the special police forces pictured on a roof top near the scene of searchings at a house IN Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, Brussels. Credit : Belga/ James Arthur

Credit : Belga

Abdeslam fled to Brussels and vanished for four months. His prints and DNA were later found in a Forest district flat. A botched raid on 15 March 2016 exposed his hideout. Police caught him three days later in Molenbeek.

But the Paris cell was not finished. Other members, including bomb-maker Najim Laachraoui, were already preparing new attacks.

At least three of the Brussels bombing suspects were either Belgium nationals or long-time residents. Credit : Belga

Aftermath of the Zaventem Airport Attack. Screenshot

The sprawling network behind the Paris and Brussels atrocities had syphoned fighters through Greece, Hungary, Germany and Belgium, built bombs in Brussels safe houses and used encrypted apps to direct the carnage. Many members were killed or arrested in the aftermath, but several remain on Europe’s wanted lists.

An abandoned laptop found in Schaerbeek in March 2016 confirmed what detectives already suspected: the same network had planned, supplied and directed the attacks in France and Belgium, and had even scouted other targets.

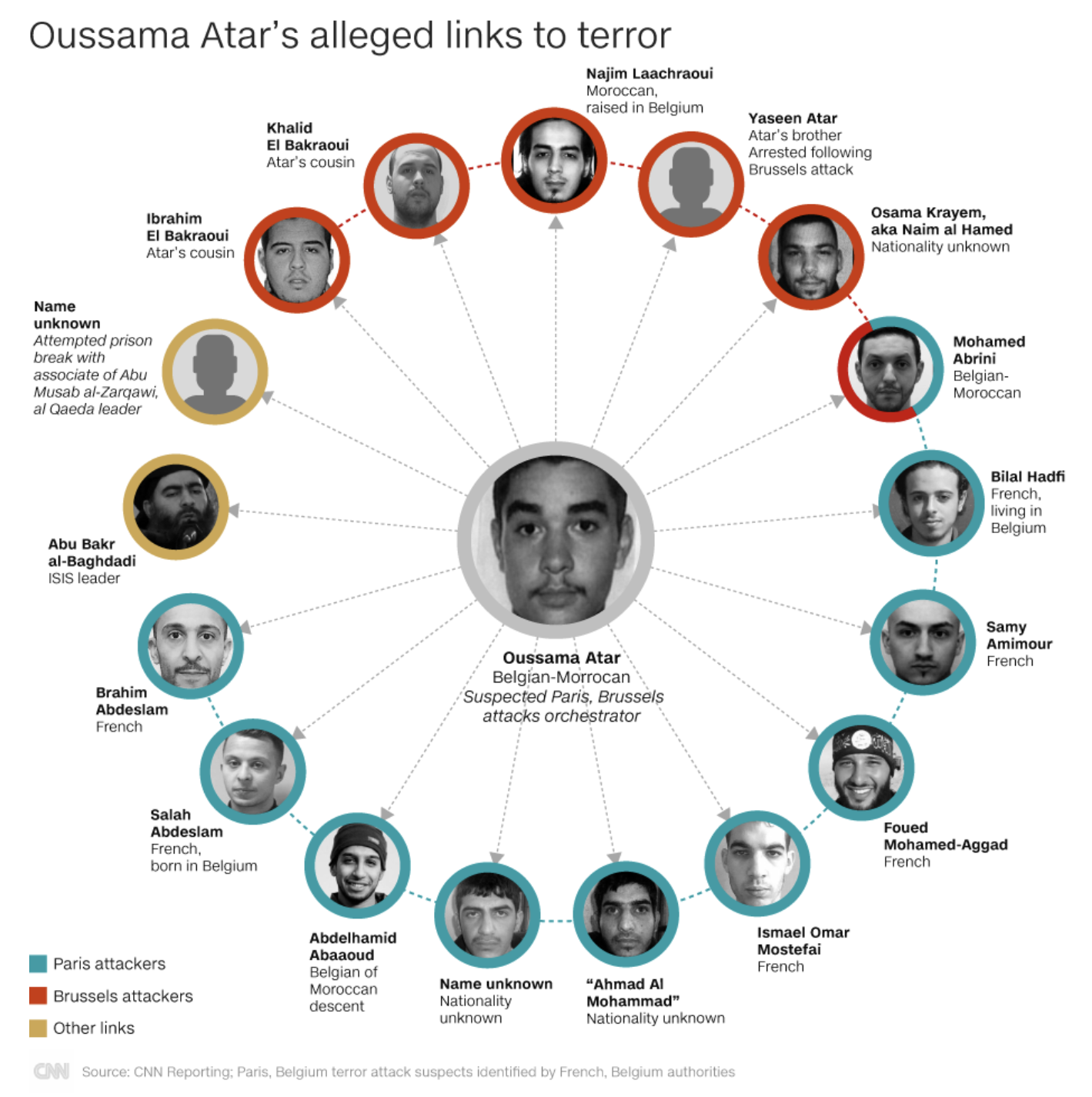

At the top of the structure sat a coordinator by the name "Abou Ahmad" or "Abou Hamza". His real identity remained unknown until late 2016, when Belgian counter-terrorism officers concluded he was likely Oussama Ahmad Atar, a Belgian-Moroccan militant aged 32.

Atar's immediate link to the Brussels bombings is through his distant cousins, Ibrahim and Khalid el-Bakraoui. The two brothers blew themselves up at Zaventem airport and Maelbeek station, respectively.

Atar's younger brother, Yassine, was also arrested around the time of the Brussels attacks, and their mother's home has been raided by police several times since the attacks.

Credit : CNN

A decade after the Paris and Brussels attacks, the question is no longer who carried them out, but what remains of their legacy.

The long judicial aftermath of the Paris and Brussels attacks culminated in two unprecedented trials, held on either side of the border. In Paris, a ten-month proceedings, the largest criminal trial in modern French history, ended in June 2022 with nineteen men convicted for their roles in the 2015 massacres.

In Brussels, a second trial followed in 2023, focusing on the 22 March bombings and the broader network behind them. Salah Abdeslam, the only surviving member of the Paris commando, stood at the centre of both cases.

During his detention in France, he managed to smuggle a USB stick into his cell, which his former partner smuggled. She was subsequently charged for illegally communicating with a convicted terrorist and for helping him circumvent prison restrictions.

Credit : Belga

This drawing by Jonathan De Cesare shows accused Mohamed Abrini, accused Osama Krayem and accused Salah Abdeslam during a session regarding the judgment on the penalty at the trial of the attacks. Credit : Belga

Salah Abdeslam pictured during a session of the trial of the attacks. Credit : Belga/ Laurie Dieffembacq

Salah Abdeslam pictured during a session of the trial of the attacks. Credit : Belga/ Laurie Dieffembacq

What now?

To understand how Paris and Brussels have absorbed the shock, The Brussels Times spoke with political scientist and Belgian radicalisation expert Sébastien Boussois, and drew on reflections from both Paris and Brussels prosecutors quoted in Le Soir who dealt with the situation hand in hand.

In October, Belgian authorities foiled a suspected terror plot targeting Prime Minister Bart De Wever. The plan, allegedly hatched by radicalised youths linked to extremist circles online, was a reminder that the threat has not disappeared.

"Today, the threat hasn't disappeared, only scattered," said Boussois. "Jihadism has become an atmosphere rather than an organisation, listed now alongside far-right extremism, eco-terrorism and conspiracy movements," he added.

"'Never again' has lost much of its power. These terrorists were 'children of the Republic' who never felt part of it. That's the real fear: that part of the nation could turn its weapons inward." He concluded.

"We never truly came out unscathed from that period," said François Molins, France's former prosecutor-general, to Le Soir. "The threat remains, even if its form has changed."

France and Belgium lived two years under emergency rule, and their anti-terror laws grew tougher. "The challenge now," he added, "is finding a balance between reason of state, legal reason and the protection of freedoms."

Belgium's federal prosecutor Frédéric Van Leeuw warns that the same powers created to fight jihadism are now being used against migrants and minor offenders.

"That's the danger," he said to Le Soir. "Once barriers fall, everyone wants to use them."

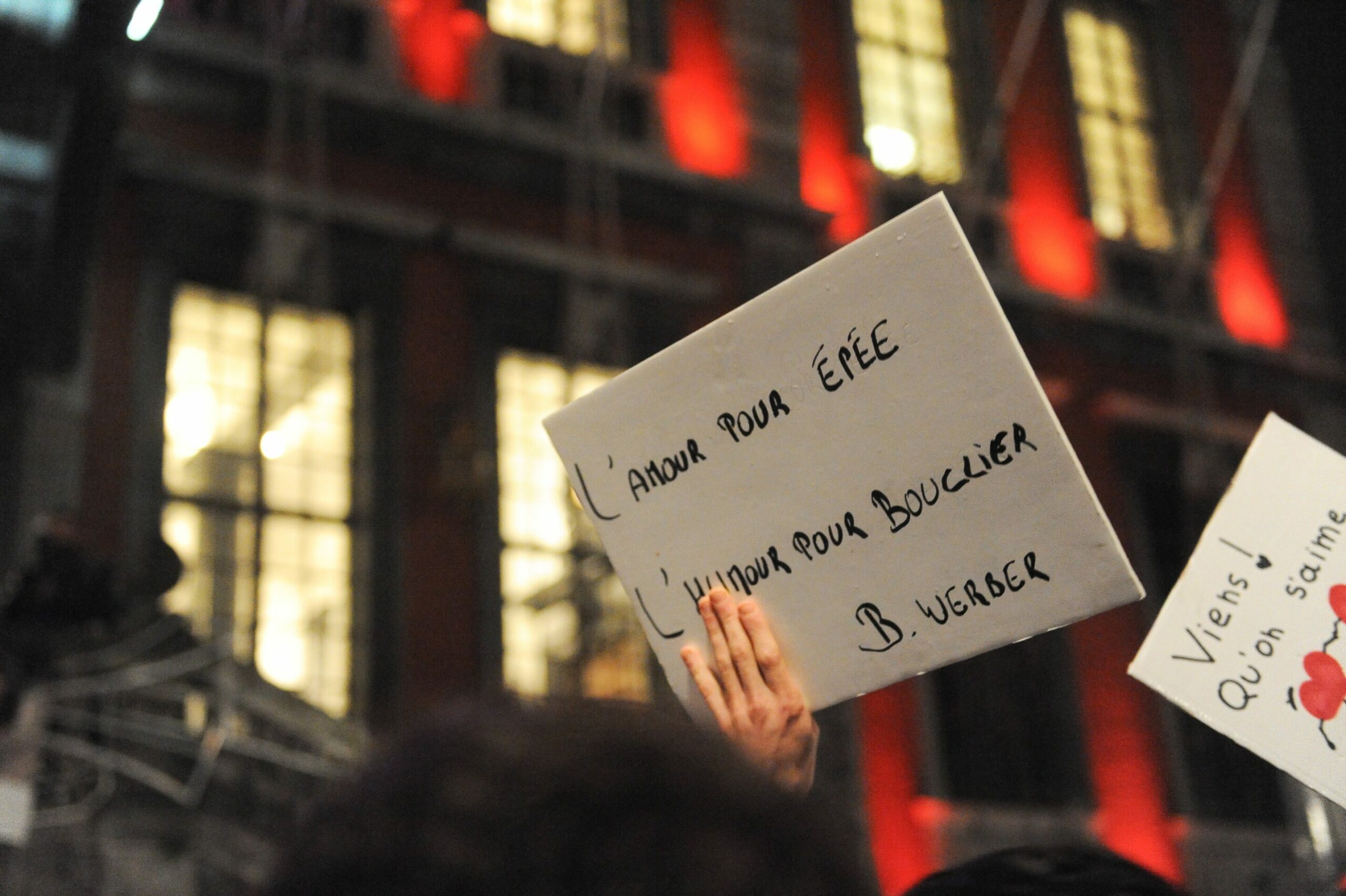

People attending a wake to commemorate the victims terrorist attacks in Paris, Tuesday 17 November 2015, at place du Marche in Liege. Credit : Belga/Sophie Kip